Labor Protests -- Gilded Age

Strikes have played a significant role in the economic, political, and social life of the United

States throughout its history. From strikes by shoemakers, printers, bakers, and other

artisans in the era of the Revolution through the bitter airline strikes two centuries later,

workers repeatedly tried to defend or improve their living and working conditions by

collectively refusing to work until specific demands were met.

Since the early 1880s, when reliable statistics were first compiled, American workers have

struck with a frequency roughly equal to that of their peers in Europe. Strikes in the United

States, however, have tended to last longer than elsewhere, with a mean duration between

1881 and 1974 of twenty days. Accordingly, the total number of workdays lost in strikes

proportionate to the size of the work force has been higher in the United States than almost

anywhere else in the world.

The United States also has had the bloodiest labor history of any industrial nation. The first

strike fatalities were two New York tailors, killed in 1850 by police dispersing a crowd of

strikers. Since then, according to one estimate, well over seven hundred people - mostly

strikers - have died in strike-related violence, and the total may be much higher. Some died

in famous incidents, such as the 1913 Ludlow Massacre, when National Guardsmen attacked a tent colony of striking Colorado miners, or the 1937 Memorial Day Massacre,

when ten supporters of a steel strike were killed by Chicago police. Most, however, died in

little-noted confrontations with company guards, private detectives, scabs, or police.

Although wage disputes have been the single most common cause of strikes, workers have

walked off their jobs for many reasons, including efforts to win union recognition, shorten

the workday, gain or defend control over the work process, improve working conditions,

and protest the disciplining of unionists. Strikes have been called to exclude nonwhites or

women from jobs and, more rarely, to protest racial discrimination. Unlike elsewhere,

political strikes over non-work-related issues have been uncommon.

Strikes have played a major role in both the rise and fall of unions (though many have

occurred without union involvement). Often strikes have stimulated the formation of new

unions or union federations. The first citywide labor federations, formed in the 1820s and

1830s, grew out of strikes by artisans seeking to shorten their workday. Over a century

later, the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) was indirectly an outgrowth of a wave

of strikes by industrial workers. Conversely, failed strikes have destroyed many unions. The

American Railway Union, for example, was unable to survive the defeat of its 1894 strike

against the Pullman Car Company. More recently, the mass firing of striking air traffic

controllers by the Reagan administration led to the demise of the Professional Air Traffic

Controllers Organization.

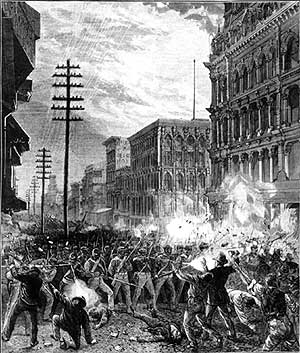

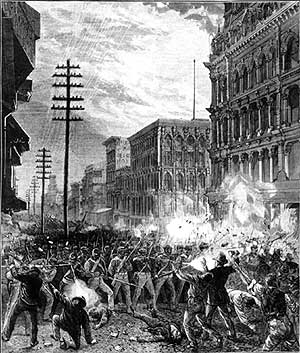

The great strike--The Sixth

Maryland Regiment fighting its way through Baltimore," Harper's

Weekly, August 11, 1877. Police, state militia, and federal

troops battled strikers in dozens of cities and towns, leaving more than a

hundred dead and thousands wounded.

The great strike--The Sixth

Maryland Regiment fighting its way through Baltimore," Harper's

Weekly, August 11, 1877. Police, state militia, and federal

troops battled strikers in dozens of cities and towns, leaving more than a

hundred dead and thousands wounded.

The Great Strike, 1877:

http://dig.lib.niu.edu/gildedage/narr4.html

- In the era of dramatic industrialization following

the Civil War, the most powerful of the big business corporations were the

railroad companies. In order to protect their profits during the economic

depression that had begun in 1873, they companies had reduced the pay of

railroad workers by ten percent.

- In 1877 they announced another ten percent

reduction in the workers' pay, and also that railroad employees would be

required to use company hotels when away from home, which meant a further

reduction in real wages. On top of this, they decided to reduce the work-force -

which meant unemployment for some and intensified labor for those remaining.

- On July 16, a spontaneous strike erupted in Martinsburg, West Virginia

and quickly spread to cities from St. Louis and Chicago to New York and

Baltimore - hitting Pittsburgh on July 19.

- To "keep the peace" and break the strike,

state militia units from Philadelphia were ordered to Pittsburgh. (Militia units

from Pittsburgh were deemed unreliable because they sympathized with the

strikers.) On July 21, six hundred troops arrived from Philadelphia. Led by

Superintendent Robert Pitcairn of the Pennsylvania Railroad and a posse of

constables with arrest warrants for the strike leaders, they found themselves

confronted by crowds of men, women and children. The crowds, loudly protesting

the troops' presence and expressing support for the strikers, sought to prevent

military action. The militiamen responded with a bayonet charge that resulted in

injuries and provoked a hail of rocks from some sections of those assembled. The

troops then opened fire on the unarmed men, women, and children, scattering them

- and leaving at least twenty dead (including one woman and three small

children) and twenty-nine wounded.

- Workers

from other cities and towns in Pennsylvania joined in the strikes or in rallies

and meetings supporting the strike. General strikes, mass demonstrations, and

sometimes violent confrontations rocked cities in many other states as well,

though none exceeded the violence of the Pittsburgh battles.

- On July 26, however, regular troops of the U.S. Army

joined with state militia units to take control of the city and reopen all

railroad operations in Pittsburgh and Allegheny City. The strike was

systematically broken throughout the country by similar means by the end of

July. This was the first time in U.S. history that federal troops were utilized

against strikers and labor protests

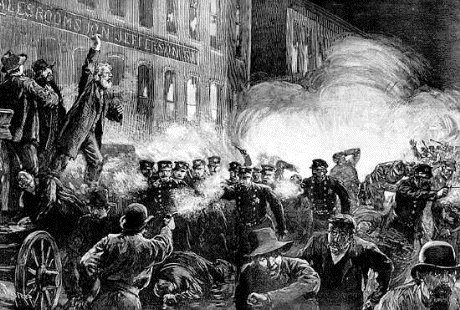

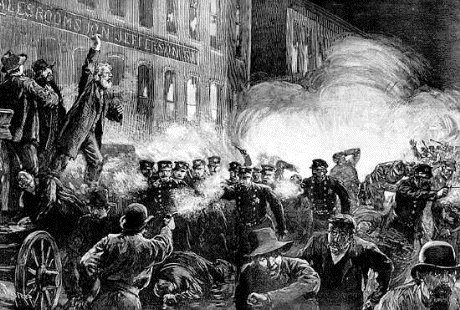

Sketch

by Thure de Thulstrup (Harper's Weekly

5/15/1886)

Sketch

by Thure de Thulstrup (Harper's Weekly

5/15/1886)

The Haymarket Strike:

http://www.kentlaw.edu/ilhs/haymkmon.htm

- Powderly called for the Knights of Labor to participate in

a planned one-day strike on 1 May in support of the eight-hour day. (40,000

to 60,000 participated). 3 May -- six strikers were killed at the McCormick

Reaper Manufacturing Company, after police fired into the crowd who had

attacked strikebreakers

- 4 May -- 13 - 1400 participated in a meeting at

Haymarket Square, called by anarchist August Spies, Knights of Labor, and

many socialists unions and international anarchists, protesting the use of

police force to disperse strikers.

- At 10 P.M. when 180 police arrived to order the crowd out,

a bomb thrown into their midst killed 7, and wounded at least 60. It

was assumed that an anarchist threw the bomb and raids were conducted on all

known radical groups, including trade union leaders.

- Judge Joseph E. Gary presided over the trial of Samuel

Fielden, speaking when the bomb was thrown, August Spies, Albert Parsons,

Michael Schwab, Adoph fisher, George Engel, and Oscar Neebe, who were

charged with conspiring to kill.

- Although no evidence linked specific persons to the

incident, the prosecution focused on their radical beliefs and advocacy of

violence to achieve goals. This political trial resulted in 7 convictions

(the 8th defendant hung himself).

- Four were sentenced to death (Spies, Parsons, Fisher,

Engel), two to life in prison (Fielden, Schwab), one to 15 years (Neebe).

They are found guilty on the grounds that it is not necessary to plan a

murder for members of a conspiracy to

be murderers or accessories before the fact As a result, an

anti-radical and anti-union feeling swept the American public mind.

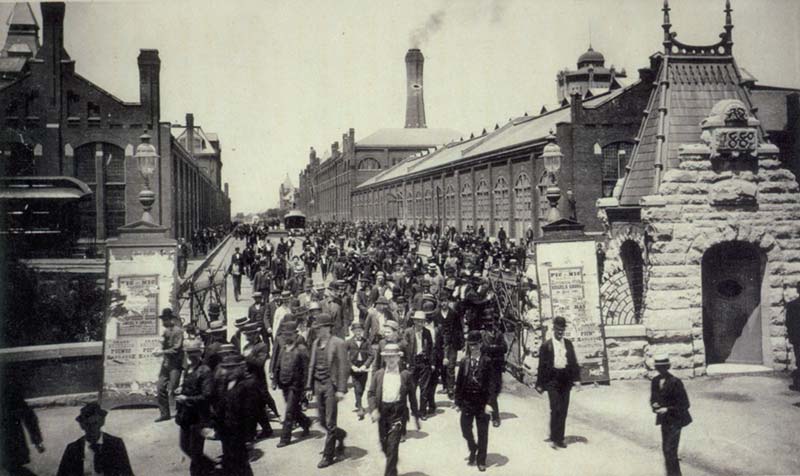

1892

- Illustrated Weekly - Labor troubles at Homestead, PA

1892

- Illustrated Weekly - Labor troubles at Homestead, PA

Homestead Strike - July 1892:

http://oak.cats.ohiou.edu/~mk247899/info-pub.htm

- 5,000 steelworkers struck Andrew Carnegie's steel plant near Pittsburg PA.

- A pitched battle erupted between the strikers and 300 Pinkertons hired by plant manager Henry Clay Frick

who had been hired to protect the strikebreakers. Seven guards were killed.

- 9 July - 7,000 state troopers were sent in by Governor Pattison. 15 July - the steel mill was reopened by strikebreakers. By Nov 14, Frick had broken the 24,000-member Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers and

the strike ended.

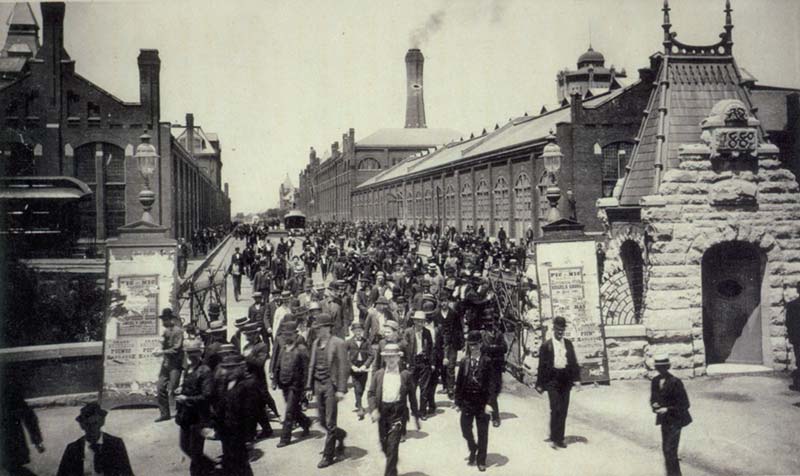

Pullman

workers exit the factory gates after a day's work. Most employees walked the

short distance to their nearby Pullman-owned homes and apartments.

Pullman

workers exit the factory gates after a day's work. Most employees walked the

short distance to their nearby Pullman-owned homes and apartments.

Pullman Strike - 1894:

http://ehistory.osu.edu/osu/mmh/1912/content/pullman.cfm

- George Pullman , Pullman Palace Car Co., had established a model town for his workers near Chicago

which promoted a clean healthy atmosphere, giving Pullman a public image as a benevolent, paternalistic industrial

captain.

- The panic of 1893, worse in US history at that time, caused a wage cut by 1/3, but no lower rent on company

housing nor price reduction at company stores. When Pullman fired a suspected union organizer, a strike grew ugly by 1894.

- Eugene Debs , leader of the American Railway Union , aided strikers by refusing to handle railroads using

Pullman cars, encouraging other unions to join.

- The strike was ended by a court injunction, based on the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, after which President

Cleveland sent in 10,000 federal troops (because of "interference" with the US mail), who along with 2,000 state

troops smashed the ARU.

The great strike--The Sixth

Maryland Regiment fighting its way through Baltimore," Harper's

Weekly, August 11, 1877. Police, state militia, and federal

troops battled strikers in dozens of cities and towns, leaving more than a

hundred dead and thousands wounded.

The great strike--The Sixth

Maryland Regiment fighting its way through Baltimore," Harper's

Weekly, August 11, 1877. Police, state militia, and federal

troops battled strikers in dozens of cities and towns, leaving more than a

hundred dead and thousands wounded.

Sketch

by Thure de Thulstrup (

Sketch

by Thure de Thulstrup ( 1892

- Illustrated Weekly - Labor troubles at Homestead, PA

1892

- Illustrated Weekly - Labor troubles at Homestead, PA